Estimated time to complete this section: 4 minutes

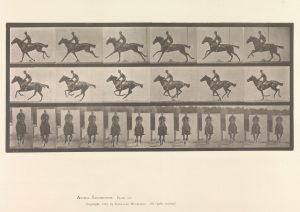

Evidence of the idea that still images can be sequenced to create the illusion of movement goes as far back as 150 BCE. However, we usually point to the experiments of late-nineteenth century photographer Eadweard Muybridge as the beginning of what we call motion pictures today. In the 1870s, Muybridge constructed motion studies using a number of still cameras.The cameras’ shutters were released by trip wires activated by the movement of Muybridge’s subjects–which included cats, birds, and most famously, a race horse. Using a device called a zoopraxiscope, Muybridge was then able to project the motion studies for audiences.

These projections led the way for inventors of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to refine and combine the photographic and projection functions needed to create the motion picture. Today, a variety of film formats may be present in library holdings, such as:

- Documentaries

- Feature films

- Newsreels

- Personal footage (e.g., home movies)

In examining the process of creating films, however, we should also consider and understand that what we are viewing has been mediated in one mode or another; while films are commonly understood to be objective forms because they captured events as they were unfolding, they do not document historical moments on their own. The events or scenes may or may not have been staged; the images pass through a camera; those images might have been trimmed and combined to create the final product we see.

Appreciating that film is a mediated source does not imply that it should be excluded from being utilized as historical evidence. Film sources and their components (dialogue, clothing, setting) can be analyzed for their depictions of social attitudes within a period. In order to fully analyze film sources, you will need to be sure to use other sources (e.g., reviews, letters, fan magazines, oral histories).

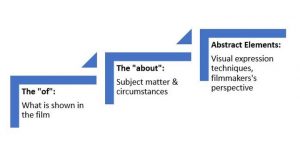

Consider this thought process for analyzing film sources: The thought process in analyzing film is similar to that for photographs:

adapted from Elisabeth Kaplan and Jeffrey Mifflin, “ ‘Mind and Sight’: Visual Literacy and the Archivist,” in American Archival Studies, ed. Randall C. Jimerson (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2000), 73-97.

| The “of”: | Who created the film?

What do you see? How are people/objects displayed? |

| The “about”: | When was the film made?

In what historical context can you place the film? |

| Abstract Elements | Why was the film made?

What techniques were utilized to create the film?

From what perspective is the film shot? Who is the intended audience? How might the identity of the intended audience impact the way the film was received? If there is music, commentary, or dialogue, how do they influence the nature of the film? |

| The questions above will provide a starting point for analysis. However, different film genres require additional analysis specific to the format: | |

| Documentary | What additional sources can be used to determine the accuracy of these reconstructions?

Is the documentary a primary source, or is a secondary source? |

| Feature Film | In films ‘based on” or “inspired” by real stories, events might be reordered to fit a dramatic narrative:

How might this reshape understanding of the historical event? What kind of research was conducted? What is the message of the film? Does it tell us something about the time it was made or the time it was set? Both? How does the purpose of the film affect its utility as a primary source? |

| News | Where is the news information coming from?

What point of view is presented? What local values and concerns are reflected from the news footage? Which are absent? |

| Personal Footage | How representative are home movies of everyday lives? Whose stories are being told? Whose aren’t? Why might this be the case?

How might footage of personal, family, community events be useful as historical sources? |

adapted from Tom Gunning, “Making Sense of Films,” History Matters: The U.S. Survey Course on the Web, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/film/, February 2002.