Estimated time to complete this section: 1 hour 45 minutes

2.2 Readings:

- Abbott, Franky. “Understanding Copyright.” Public Library Partnership Program, Digital Public Library of America, 2015 (Video time = 1 hour)

- Russell, Judy G. “A terms of use intro.” The Legal Genealogist (blog), April 27, 2012 (Estimated Read Time = 5 minutes)

The easy access to material offered on the web can create a sense that what you find online is available for you to use in any way you want. To the contrary, digital material published on the web is covered by copyright law in the same way as analog forms of material. As you work with digitized archival materials, it is important for you to remember that the owner of the materials may have legal rights to restrict your use or publication of them. Copyright law allows archives and libraries to provide copies of material for use in private study, scholarship, or research. However, you may need to get permission of the copyright owner before publishing digitized material. Remember, putting material on a publicly accessible website constitutes publication.

Making a decision about online material thus requires both an evaluation of the material and of the site on which it appears. National repositories, like those explored in 2.1, often include rights statements and define the rights of each item. You should seek out this information to ensure that your use is appropriate.

Unfortunately, there is considerable variation in the form and contents of the rights information provided by archives and libraries, and it is not always clear who owns the rights to material. Archives do not automatically own the copyright of material in their holdings. Donors or sellers can retain the rights for material, or they may not own the copyright of all the items they transfer to an archive. For example, a donor may not own the copyright to letters written to them, or they may have transferred the rights to someone else, such as a publisher (see SAA, FAQs).

Material in archives may also not be under copyright, a status referred to as being in the public domain, which means it can be used freely without permission or attribution. Copyright cannot be claimed over digital images of public domain material; you need to alter the work to be able to claim copyright. However, your use of digitized public domain material can be restricted by terms of use, such as those you agree to in order to use subscription-based databases such as Newspapers.com or Ancestry.com.

- Terms of Service – Many archives have rights statements that you have to read, acknowledge, and sign before you see any materials. Similarly, digitized material viewed online often include terms of service that visitors automatically accept by using the site. For instance, see the Ancestry.com Terms and Conditions page, which also covers Newspapers.com, which state:

“In exchange for your access to the Services, including the DNA Services described below, you agree…Not to resell the Services or to resell, reproduce or publish any content or information found on the Services”

- Usage Rights – Archives and libraries often include the rights information in the metadata for objects available online. Take for instance, this copy of the Negro Motorist Green Book, published in 1937, in the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

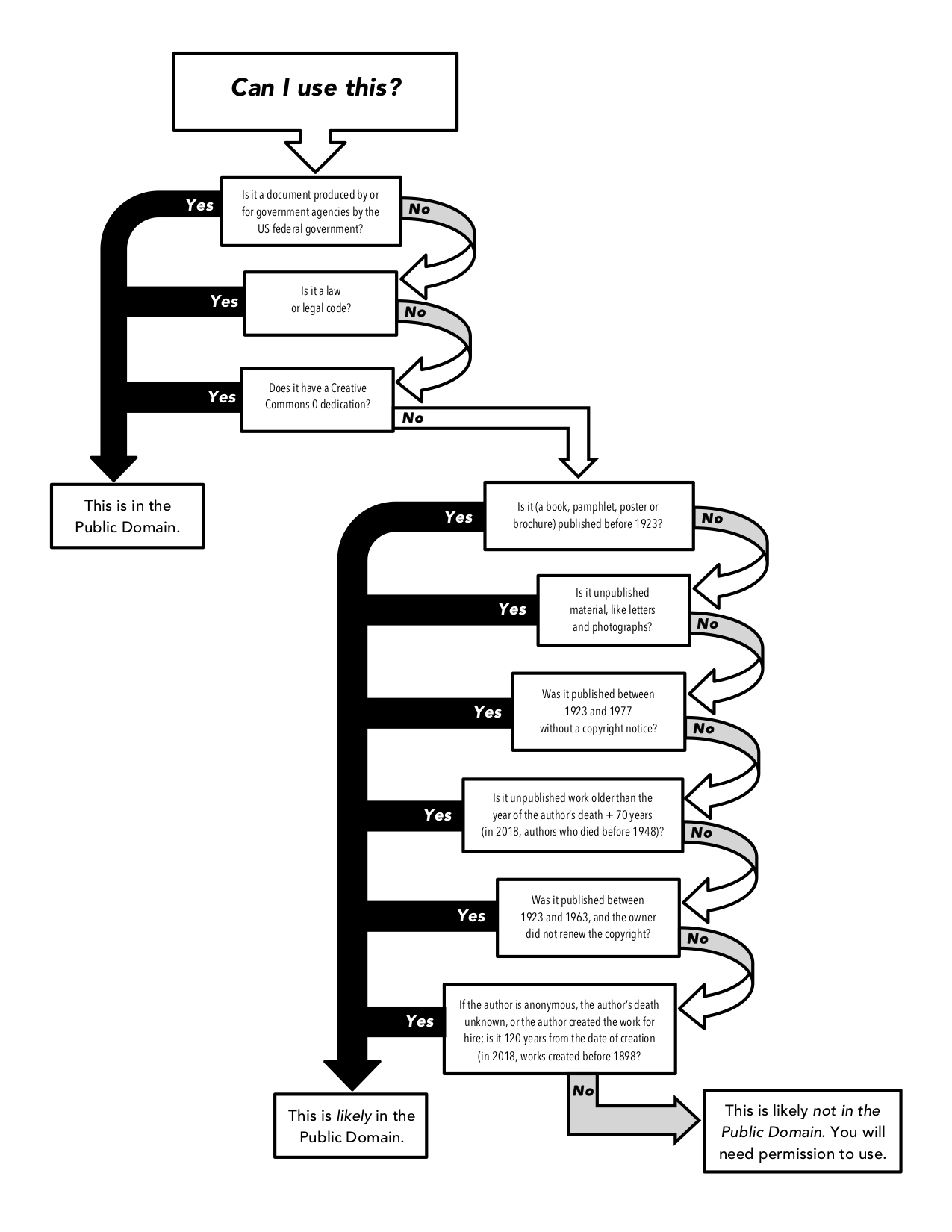

As you read in Abbott and Russell, determining copyright and identifying items in the public domain can be a complex process. Use the following information as a guide for determining whether content is in the public domain. Please note: These lists apply only to U.S. copyright status. If you live or work in another country or are using material published in another country, you should check that country’s copyright policies. For more information, see American Library Association’s Copyright Slider.

Material not protected by U.S. copyright law and always in the public domain:

- U.S. federal government documents (produced by or for government agencies); note that only some state government documents are in the public domain

- Laws and legal codes

- Works whose owners waive their copyright by using the Creative Commons 0 dedication

Material likely in the public domain

- Works published before 1924 (currently, this date is moving forward, so an additional year of material begins available each January 1)

- Note: In copyright law, publication is defined as “distribution to the public,” which can include posters, brochures and pamphlets, as well as books

- In copyright law, unpublished material can include correspondence and photographs

- Works published between 1923 and 1977 without a copyright notice

- Works published between 1923 and 1963 if the owner did not renew the copyright

- Unpublished works older than the year of the author’s death + 70 years (in 2019, authors who died before 1949)

- Unpublished works older than 120 years from the date of creation, if the author’s death is not known, or if the author is anonymous or created the work for hire (in 2019, works created before 1899)

You should ensure that you include and record rights information as part of the metadata for items in your Omeka site. Both the “Source” and “Rights” fields should be used to properly attribute the material and communicate to visitors how it should be used. We recommend that you include a URL to the relevant information in your rights metadata, if one is available (see, for instance, The Stradbroke Village Archive clarifies the rights to this image of children playing with rabbits with a clear Creative Commons license; The Civil War in St. Augustine project defines both the source and rights for this 1863 letter; the Histories of the National Mall project provides information on the source for this photo of Congressional Pages playing in the snow on the Mall, as well as a link to the Library of Congress page.)

Your library may have material that is available to researchers for use on-site but not available for publication or distribution. Be sure to evaluate the ways in which your library communicates usage rights to your patrons. This may involve consulting your internal guidelines to develop clear statements for donors who contribute materials to the library or bring photos and other material for library programming.

[Our thanks to Tropy and the Public Library Partnerships Project for this section.]

Activity 2.2: Identifying Online Material You Can Use

In this activity you will assess whether three online sources are under copyright or in the public domain and freely available for use. In order to determine whether the content is in the public domain, use the following questions to guide your assessment:

- Is the work published?

- Has the copyright expired?

- Was the work published without a copyright notice?

- Has the copyright been renewed?

- Has the copyright owner placed the material in the public domain?

- Is this type of work protected by copyright?

- Do you have to agree to terms of use when you access the material? Do those terms of use restrict you from publishing the material?

Finally, answer the question: Can this material be used freely without permission or attribution?

Source 1: Sweet Cicely or Josiah Allen as a Politician (1885)

Source 2: Silent Worker newspaper (1911)

Source 3: Arrival of emigrants [i.e. immigrants], Ellis Island

Source 5: United States Census, 1860, Ronald, Ionia County, Michigan, page 27.